Failure Rates Among Students Fuel Calls for Face to Face Teaching

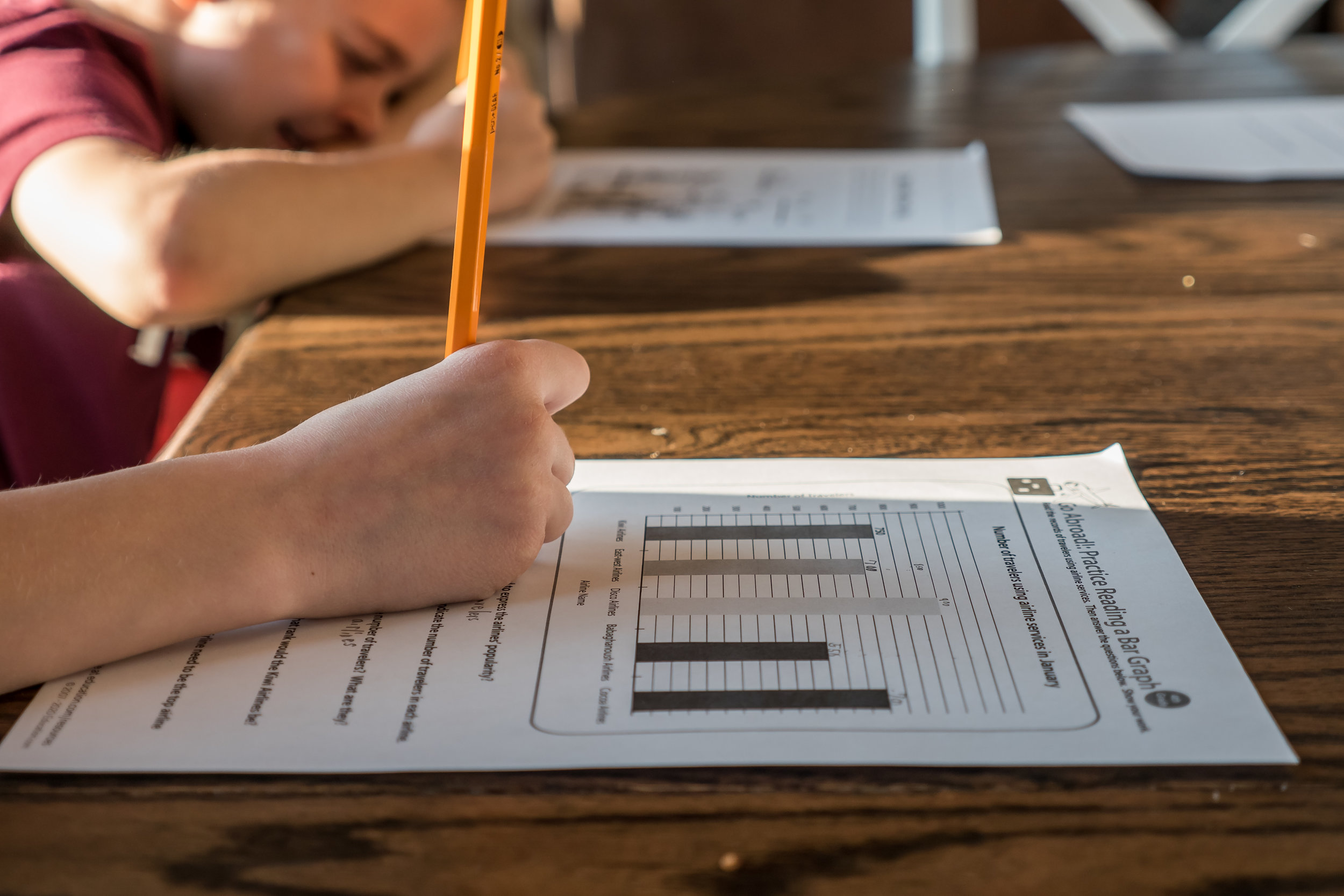

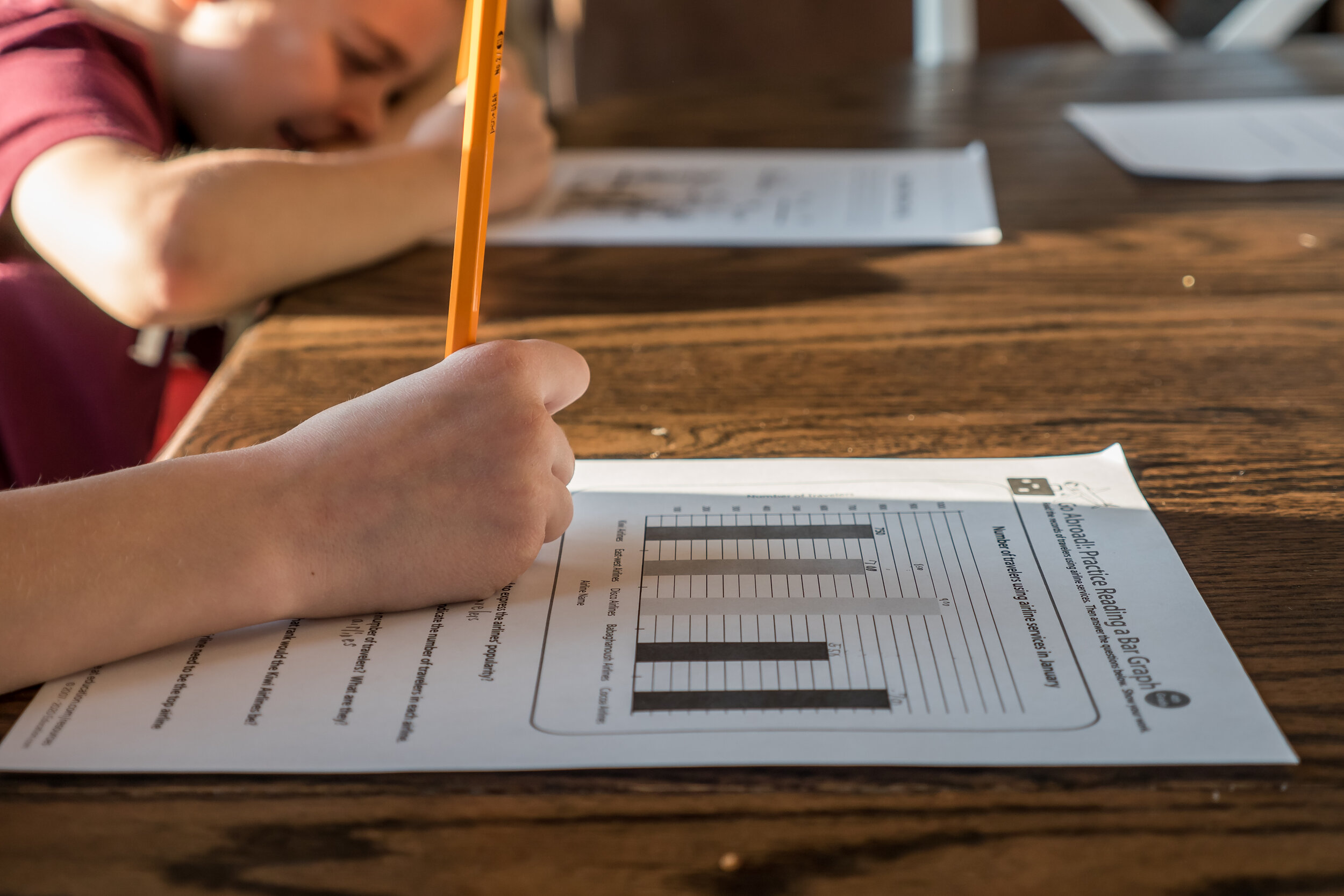

Most schools hoped this fall would see students make up academic ground lost last spring when the pandemic hit. Instead, districts are looking for ways to reverse plummeting grades and attendance among students learning at home.

Alarming failure rates among Texas students fuel

calls to get them back into classrooms

By Aliyya Swaby - October 23, 2020

As fall progresses, Texas public school superintendents are realizing that virtual instruction simply is not working for thousands of students across the state.

Report cards from the first weeks of the school year show more students than last year failing at least one class. Students are turning in assignments late, if at all; skipping days to weeks of virtual school; and falling behind on reading, educators and parents report. Many parents say they’re exhausted from playing the role of at-home teacher, and some students without support at home are struggling to keep track of their daily workload with limited outside help.

The problems are concentrated among students trying to learn from home, more than 3 million of the state’s 5.5 million public school students, according to administrators’ accounts. The trends are adding urgency to calls for getting more students back into classrooms as quickly as possible.

By now, many school districts hoped their students would be making up academic ground lost last spring, when the pandemic caused them to shut down classrooms. Texas is mandating that districts get back to normal this fall and prepare students for upcoming state standardized tests. Schools dialed up the intensity of their classes — and then an alarming number of students began failing.

As the first grading period came to a close, some administrators began temporarily backpedaling from their initial insistence on academic rigor. They gave teachers the message: Do what you can to make sure kids pass.

Judson Independent School District, in San Antonio, added a note to its grading handbook allowing principals to “grant any exceptions” and “extend grace” to students, letting them make up late work or drop assignments. “We understand that connectivity issues, lack of devices, technological issues with the Student Portal, Canvas, and electronic books may impede a student from submitting their assignments in a timely manner,” the handbook now reads.

Cathryn Mitchell, principal of Austin ISD’s Gorzycki Middle School, sent an email in early October, obtained by The Texas Tribune, alerting all staff to a “campus-wide dilemma.” Almost 25% of students were failing at least one class, including 200 failing more than one subject. She attributed the failures to steep technology learning curves, lack of access to devices and Wi-Fi, shifting reopening guidelines and anxiety over the health risks of on-campus learning.

The email implored teachers to exhaust “all measures to assist the student before failing them,” including working with them one on one, emailing or calling parents, and setting up Zoom parent conferences. For teachers unable to do everything to help a failing student before the grading deadline, Mitchell wrote, “we would ask that you gift the student with a 70.” Texas’ “no pass, no play” rule prohibits students pulling less than a 70 in one or more classes in a marking period from playing sports or participating in extracurricular activities for three weeks.

“We know that some students are taking advantage of the situation or have procrastinated to get themselves into this position. There is no question about that,” Mitchell wrote. “But we also know that we have asked a great deal of them these first five weeks. ...This will not be the norm every six-weeks."

Austin ISD officials told the Tribune that school leaders are “committed to high standards of academic rigor” and working to “better serve” students with low averages or incomplete grades based on their individual needs. They did not respond to questions about whether Mitchell’s approach was supported by the district or whether 25% is an average failure number across the district this marking period. According to KVUE-TV, about 11,700 Austin ISD students are failing at least one class this year, a 70% increase from last year.

As the extent of students’ struggles become clear, parents and superintendents are increasingly determined to get students back to school, the pendulum of their worries swinging away from health risks and toward the risks of students not learning at all. “Districts are starting to feel some real internal pressure as educators,” said Joy Baskin, legal services director at the Texas Association of School Boards. “If they feel that there’s enough momentum around getting everyone back, I think that’s their preference.”

State data on COVID-19 in schools is limited and full of gaps, but it points toward low student infection rates, encouraging some experts. Experts say layering policies such as sanitization, social distancing and masks is needed to reduce the risk of transmission. Despite outcries from some teachers and parents, dozens of school districts have nixed their virtual learning options altogether and brought nearly all students back to classrooms.

According to the San Antonio Express-News, at least one of those districts is attempting to require all remote learners with failing grades to return in person — violating recently updated state guidance. “Discontinuing remote instruction in a way that only targets struggling students is not permitted,” the updated guidance reads.

Texas school districts don’t have much time to get students back on track. This academic year, the Texas Education Agency will resume strict sanctions on schools and districts with consistently low student standardized test scores after pausing those penalties last spring. And there are dollars at stake, with state funding tied to student attendance. Districts have reported losing track of thousands of students, including some of their most vulnerable, who haven’t logged into virtual classes or responded to phone calls and door knocks. According to state leaders, schools that are open for in-person instruction have seen higher levels of enrollment than those with only virtual education.

San Antonio’s Northside ISD has not changed its expectations for virtual students, despite seeing higher failure rates, said Superintendent Brian Woods. Since many students learning from home are low income, Black and Hispanic, lowering academic standards for those students could end up deepening existing inequities, he said.

Instead, the district has put together a call team to reach out to low-performing virtual learners and urge them to come back to campus. Just under 45% of students are learning from classrooms in the second grading period, up from less than 25% earlier in the fall, when the district slowly phased students in. “We’re not going to fix it by only taking the good grades or dropping half the grades,” Woods said. “We’ve got to dig in and look more at the root cause. We know what it is: There’s kids who need to be in the building, period.”

In Brazosport ISD, where 78% of students are learning in classrooms, a quarter of virtual learners are failing two or more classes, compared with 8% of at-school students. The district is “not dropping our expectations for at-home students,” said Superintendent Danny Massey. But with coronavirus cases dropping in Brazoria County and district officials being transparent about COVID-19 cases on campuses, more parents are gradually choosing to send their students back. Some Austin ISD parents are considering sending their children back later this fall, once the district returns to in-person instruction that more closely resembles a regular classroom. When the district reopened, it had students sitting in classrooms but learning virtually. The state halted that approach. Rosemary Wynn, an Austin ISD parent, thinks her eighth and ninth grade sons may get more out of learning in person once it includes more face-to-face instruction.

She and her husband had a stern talk with their O. Henry Middle School eighth grader earlier this fall after realizing he had not opened about 100 emails from his teachers, except one from his football coach. He was previously a straight-A student, but at one point his grade in one class had fallen to 29, she said. “Children don’t know how to read email. That is not part of their repertoire,” she said, with exasperation. “I haven’t had a single teacher reach out to say, ‘your kids’ grades this, your kids’ grades that.’ I think the whole way this is set up is a recipe for disaster.”

Kelly Sanders and her son Bizuayehu Crouther, a 14-year-old at Austin High School in Austin ISD, regularly debate whether he should return later this fall. Bizuayehu has dyslexia and dysgraphia, which impacts his ability to write clearly by hand, and he’s found virtual learning much easier. “I do not want to go back,” he said.

Sanders is concerned that the second grading period will be even more academically rigorous and that her son will not be able to keep up virtually. “I’m happy that [he is] making really good grades right now, but I’m concerned that it still isn’t as rigorous as the classes would be if it were in person. If at some point he has to take a standardized test on the material, I don’t know what that looks like,” she said.

But for other parents, the decision is easy. Single parent Renee Schalk chose to keep her 17-year-old son and 2-year-old triplets home from Georgetown schools and doesn’t regret it. “My children are children of color,” said Schalk, who is Black. “I don’t want them subjected to COVID-19. … We’re not doing enough in this state, we’re not doing anything in this country to make it safe.”

Angelina Allegrini, a 14-year-old ninth grader in San Antonio’s North East ISD, said her grades suffered in the beginning of the year as she got accustomed to the variety of programs teachers used for online learning and the exhaustion of staring at a screen for three to four hours a day. After a few weeks, and a little leniency from teachers, she pulled them back up.

But the social, extroverted teenager still felt she was missing something. “I wanted to try to get to know people in my class. I saw some of them on the screen, but that’s not the same,” she said.

On Monday, after several weeks of learning from home, Angelina walked into her high school for the first time this year. Her mother, Cherise Rohr Allegrini, a prominent epidemiologist in San Antonio, said she was “not thrilled” about her daughter’s decision but predicted it wouldn’t last long, with a surge in COVID-19 cases likely on the horizon. “I think they’re probably going to change and close schools in a couple of weeks or so,” she said. “We’re going to start seeing outbreaks on campuses.”

Wi-Fi Buses

As more students return to school in person, some school districts are having to trim back programs that deployed buses as hot spots in neighborhoods for students with little or no internet access.

Wi-Fi buses were a quick solution for student internet access, but as schools reopen they need their buses back

"Wi-Fi buses were a quick solution for student internet access, but as schools reopen they need their buses back" was first published by The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization that informs Texans — and engages with them — about public policy, politics, government and statewide issues.

Need to stay updated on coronavirus news in Texas? Our evening roundup will help you stay on top of the day's latest updates. Sign up here.

The sight became familiar across Texas after the coronavirus pandemic abruptly closed schools last spring — empty school buses rigged with Wi-Fi routers sat in parking lots and neighborhoods, allowing students to tap into free internet to do their schoolwork.

But with more students returning to in-person classes, some school districts now need to get those buses back on the road while still figuring out how to provide internet access to families needing it.

The Austin Independent School District has been deploying 261 Wi-Fi-equipped buses across 40 neighborhoods with little or no home internet access, said Eduardo Villa, a district spokesperson. Drivers not needed to haul loads of students to school and away sports events stationed their buses as internet access points on weekdays from 7:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m, said Kris Hafezizadeh, the district’s executive director of transportation.

Austin's schools reopened for in-person classes Monday. While bus drivers will still have Wi-Fi duty, the hours will be squeezed between morning and afternoon routes — roughly 4-hour shifts in the middle of the school day.

Families relying on the buses for internet will now have to request free hotspot devices from the district, which has about 8,000 of them left to give out, Villa said.

Wi-Fi bus programs were an affordable, quick-turn solution to long-standing problems getting students in rural and underserved neighborhoods access to the internet.

Students learned which spots in their homes were within Wi-Fi reach. Parents called bus drivers and asked them to please move the bus a few feet closer, or shift a bit to the left so their child’s’ school-provided laptop could catch the signal. Some parents packed sandwich lunches and spent hours in the car with their kids parked next to what was a hulking yellow internet router.

But it was meant to be temporary, internet access experts said.

“I look at it as very much exactly like a band-aid type of solution. You stop the initial bleeding until you can figure out what the long term plan is,” said Brian Shih, principal network consultant at the EducationSuperHighway, an organization focused on bringing internet access to public school classrooms.

Southside ISD, in the more sparsely populated southern reaches of San Antonio, initially reopened its schools at one-quarter capacity. For now, the district can still spare buses and staff for the Wi-Fi program, but that won’t be the case soon, said Jesse Berlanga, the district’s transportation director.

Of the district's 41 buses, 15 have been serving as hot spots. As schools allow more students to return to class in person, the district will have to cut hours and may cut the program to the five most popular bus hotspots, Berlanga said.

At its peak, the program served about 180 households a day, but the number hovered in the 70s over the last week, he said.

Students in households with limited or nonexistent internet access were among the first group, along with students with disabilities and English language learners, given the option to return to schools in person.

The district ordered mobile hot spots for households that chose to stick with online learning, but 130 internet-less households are still on the waiting list for a device. For now, the district will hand-deliver printed learning packets to students’ homes.

But even with the mobile hot spots in hand, some students will be left out. The hot spots work well in urban and suburban districts with plenty of cellphone towers. But they’re virtually useless in rural areas with no towers to capture a signal.

“I think that's probably the most important thing to understand, especially with school connectivity, is that every community is going to be different and require different solutions,” said Jennifer Harris, state program director for Connected Nation Texas.

This article originally appeared in The Texas Tribune at https://www.texastribune.org/2020/10/08/schools-internet-buses/.

The Texas Tribune is proud to celebrate 10 years of exceptional journalism for an exceptional state. Explore the next 10 years with us.

Private schools in Texas limit enrollment

Dependent on tuition money, private schools are eager to get children back into their classrooms. But they know inadequate safety measures could make them vulnerable to lawsuits.

Private schools in Texas limit enrollment as they aim to reopen classrooms

"Private schools in Texas limit enrollment as they aim to reopen classrooms" was first published by The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization that informs Texans — and engages with them — about public policy, politics, government and statewide issues.

Need to stay updated on coronavirus news in Texas? Our evening roundup will help you stay on top of the day's latest updates. Sign up here.

While debate about how to safely reopen public schools in Texas raged through the summer, Kim Olstrup was preparing to bring students back to her Midcities Montessori private school in Bedford. She bought an electrostatic disinfection device similar to one used on airplanes and halved enrollment from about 130 students to about 60 to accommodate social distancing in her classrooms.

In two weeks, her school for children in preschool to 12th grade will be open to students. Olstrup is optimistic enough about her precautions that she didn’t even consider turning to virtual learning as an option.

Private schools weighing whether to reopen their campuses as the coronavirus pandemic continues face a different calculus than their public counterparts. The fewer students in classrooms, the more income lost. But if they fall short on safety, private schools are more vulnerable to lawsuits than public schools.

Texas has about 900 accredited private schools that served about 250,000 students last academic year, according to the Texas Private Schools Association. Even with many Texas parents desperately seeking schools to take their children, private school enrollment is expected to drop for the next academic year, industry leaders and school leaders say.

But even with tuition income likely to go down, many schools are spending money they hadn't budgeted for safety measures like disinfectants and personal protective equipment and buying online learning software.

Texas is set to receive almost $1.3 billion from the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund, the largest pot of money allocated for local education agencies — which includes public school districts and charter schools — under the CARES Act, said Morgan Craven, national director of policy, advocacy and community engagement for the Intercultural Development Research Association.

Private schools will get some of that money, but it's unclear how much. Public schools usually have to set aside a portion of federal money for “equitable services” for private school students. The calculation is made based on how many low-income students go to private schools.

But a new rule from the U.S. Department of Education gives school districts the option to distribute the federal money based proportionally on how many district students attend a private school regardless of income. By adding caveats to how the federal money can be used, the department has made it more difficult to choose the option that only funds low-income students and effectively increases how much federal funding a private school can receive, Craven said.

The latter option means Texas’ private schools could potentially get up to $44.2 million in federal funding, while the former would allocate about $5.5 million to private schools — about a more than $38 million difference.

While school districts are still deciding how they’ll share funds, so far most school districts have chosen to distribute them proportionally, said Laura Colangelo, executive director of the Texas Private Schools Association.

Many private schools want to reopen classrooms, administrators said, but several are cutting back the number of students they will admit as they ramp up safety precautions.

In Corpus Christi, the Arlington Heights Christian School, which has enrolled about 180 of its usual 230 kids so far, canceled its football season and morning devotional with students, said head of school Leanne Isom. Parents will also be barred from entering the building after the first two weeks of school.

And the Brentwood Christian School in Austin, which enrolls upwards of 600 students on a 44-acre campus, bought plexiglass dividers and is starting the process of deciding who should wear face shields, said Jay Burcham, the school’s president.

Although it's not required by law, private school administrators that move forward with in-person classes feel that they have to clear a higher bar for safety precautions than public schools, said Cynthia Marcotte Stamer, a Texas lawyer.

As government entities, public schools have legal protections making it more difficult to sue them. Private schools try to meet or exceed state and federal safety standards — including from the Texas Education Agency, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and their local health departments — to protect students, families, faculty and staff, since they’re more vulnerable to litigation.

While private schools don’t have to adhere to TEA guidances, they have long used them as their baseline standard of care, Colangelo said.

For months, some private school leaders like Olstrup have argued that larger campuses and classroom sizes, smaller enrollment numbers and increased safety precautions uniquely position private schools to safely reopen on a case-by-case basis even if their public counterparts don’t.

Last week, Gov. Greg Abbott and Attorney General Ken Paxton effectively cleared the way for private schools to reopen at will by announcing that local health authorities don't have the power to issue blanket orders to shut down schools preemptively in anticipation of virus spread.

Under the state's guidance, local health officials can only intervene if there is an outbreak once students return to campus, at which point they can temporarily shut down a school.

While the exact data won’t be available for months, a May survey conducted by the Texas Private Schools Association projects that private school enrollment will be down about 8% in the state for the upcoming school year, Colangelo said.

Already, at least six private schools in Texas — five Catholic and one independent — have closed down permanently due at least partly to the coronavirus pandemic, according to the CATO Institute, a libertarian think tank.

Switching to fully online classes could cost private schools a chunk of money if parents are unwilling or unable to pay as much for an online education as in-person instruction.

"Most of the time, our parents aren't going to want to pay us for a 10-month contract if they know they aren't going to start until the second month of school,” Isom said.

With new safety measures in place, some schools will just barely be able to save themselves from permanent closure, Colangelo said.

“[Schools are] taking a hit for this year's budget, hoping for next year that there's a vaccine and they can be back to full speed ahead," Colangelo said.

Disclosure: The Texas Private Schools Association has been a financial supporter of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune's journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

This article originally appeared in The Texas Tribune at https://www.texastribune.org/2020/08/05/texas-private-schools-coronavirus-reopen/.

The Texas Tribune is proud to celebrate 10 years of exceptional journalism for an exceptional state. Explore the next 10 years with us.

School Officials Will Decide When to Reopen

Abbott said the state will provide schools with personal protective equipment to prepare for the new year.

Gov. Greg Abbott stresses local school officials "know best" whether schools should reopen

"Gov. Greg Abbott stresses local school officials "know best" whether schools should reopen" was first published by The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization that informs Texans — and engages with them — about public policy, politics, government and statewide issues.

Gov. Greg Abbott stressed Tuesday that only local school boards, not local governments, have the power to decide how to open schools this fall during the coronavirus pandemic.

"The bottom line is the people who know best ... about that are the local school officials," Abbott said during a news conference in San Antonio, echoing a message he's been relaying in response to questions about the process.

Texas educators and parents have been confused about who has the power to keep school buildings closed. They have also been frustrated by conflicting messages from state and local leaders.

Abbott also said that in preparation for the new school year, the state has already distributed to schools more than 59 million masks, more than 24,000 thermometers, more than 565,000 gallons of hand sanitizer and more than 500,000 face shields. He promised schools "will have their [personal protective equipment] needs met at no cost" to them, with the state picking up the tab.

In general, he described the state's personal protective equipment levels as bountiful even as the state faces an "an even greater strain" on the supply due to the coming school reopenings and flu season.

Abbott and other state leaders have backed a legal opinion from Attorney General Ken Paxton that prohibits local health authorities from issuing blanket school closures for all schools in their jurisdiction before the academic year begins. Local school boards can decide to keep schools closed to in-person learning for up to eight weeks, with the possibility to apply for waivers to remain shuttered beyond that timeframe.

Under the state's guidance, local health officials can only intervene if there is an outbreak once students return to campus, at which point they can temporarily shut down a school.

Abbott stressed Tuesday that the policy does not mean that local health authorities are cut out of the reopening process, saying local school boards are free to consult with the health experts.

"Nothing is stopping them from doing that, and they can fully adopt whatever strategy the local public health authority says," Abbott said.

The state’s guidance has overruled orders from local health authorities to keep schools closed to in-person learning for certain periods. For example, Metro Health in Bexar County had ordered schools to remain virtual until Sept. 7.

As for the personal protective equipment for schools, the Texas State Teachers Association said it was not nearly enough.

"The governor’s optics today on PPE is a drop in the bucket, compared to what will be needed if schools are forced to reopen before it’s safe," the union's president, Ovidia Molina, said in a statement. "59.4 million masks are roughly 11 masks per student. That might get students through the first week of school."

Aliyya Swaby contributed reporting.

Disclosure: Texas State Teachers Association has been a financial supporter of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune's journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

This article originally appeared in The Texas Tribune at https://www.texastribune.org/2020/08/04/texas-greg-abbott-coronavirus-press-conference/.

The Texas Tribune is proud to celebrate 10 years of exceptional journalism for an exceptional state. Explore the next 10 years with us.

Schools Reopening in Texas

With the safe reopening of schools this fall in doubt, parents with the resources are setting up "learning pods" or seeking other options. But the do-it-yourself approach to education threatens to leave behind students of color and poorer families.

As school reopenings falter, some Texas parents hire private teachers. Others can only afford to cross their fingers.

"As school reopenings falter, some Texas parents hire private teachers. Others can only afford to cross their fingers." was first published by The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization that informs Texans — and engages with them — about public policy, politics, government and statewide issues.

Earlier this summer, Kristina Boshernitzan and a group of neighbors stood in the driveway of her Austin home for a socially distanced meeting to figure out how to take greater control of their childrens' educations.

With the coronavirus spreading unpredictably and plans to safely reopen schools shifting day by day, the parents grappled with the increasing prospect that it might be unsafe, or impossible, to send their children back to school in the fall.

Each faced difficult decisions. One neighbor's husband had stage 4 cancer, and she didn’t want her children to expose him to the new coronavirus, which they might pick up in a classroom. Another mother had young twins with lung issues. Just a cold is enough to send them to the hospital, and they can take no risk of being exposed to COVID-19.

Boshernitzan, who works full-time at a nonprofit, wanted parents to pool resources and find ways to make virtual learning easier. They discussed hiring a college student or nanny to help children complete their online school district coursework, or finding a music or arts instructor who could replace enrichment courses while schools are closed for in-person learning.

To reach even more parents, she created a private Facebook group for parents in northwest Austin who want to connect and form “learning pods,” a term she said is “in the zeitgeist right now.” In less than two weeks, the group gained almost 500 members.

Such scenes are playing out across Texas and the country as school districts delay their return to in-person instruction this fall and COVID-19 cases continue to surge. Parents will be playing an even bigger role in determining what and how their children learn, and they are deploying all the resources they have at their disposal to ensure it goes more smoothly than in the spring.

For some, like Boshernitzan, that means organizing learning pods in which families pool their money to hire an instructor and take turns hosting small groups of students to follow the school district’s learning plan at home. Others are withdrawing their children from public schools entirely and planning to home-school with learning materials they can find online for free and at cost. Some parents with younger children are sticking with trusted private child care centers that separate students and follow strict health codes.

But many parents don't have the money to hire private instructors or the flexibility to home-school their children. Upon hearing that Frisco ISD wouldn’t open classrooms for at least three weeks after the school year begins, Chloe McGlover panicked, knowing her budget is too tight to hire a tutor or full-time teacher for her 11-year-old son, Jhonte. The single mother owns a massage therapy business and lost money shutting down earlier this year during the statewide stay-at-home order.

“I already know I can’t afford it. There’s really no point in even looking,” she said. “Whatever little savings I had is almost depleted now.”

The decisions parents are making in response to the patchwork of opening dates, remote learning and do-it-yourself education coming this fall underscore the fact that the pandemic will exacerbate education gaps between higher-income and low-income students, as well as white students and students of color.

A University of Texas and Texas Politics Project poll earlier this summer showed that 65% of Texans said it was unsafe for children to return to school. Black and Hispanic Texans were more likely than white Texans polled to say it was unsafe. Available data from some of Texas’ most populous counties, including Harris County, shows Black and Hispanic Texans disproportionately contracting COVID-19.

Research published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggests there are higher rates nationally of hospitalizations and deaths related to COVID-19 among some people of color than there are among white people, and that circumstances such as being an essential worker and lacking health insurance are related to these risks.

Low-income, Black and Hispanic Texans are more likely than high-income and white Texans to be essential workers and to lack health insurance. And those families, a majority in Texas public schools, are less likely to be able to afford private supplements to their children’s education.

Some with money and resources will sprint ahead. Those without will lag behind. Thousands of families still don’t have access to the laptops and Wi-Fi hotspots they will need to learn from home this fall, and for some, keeping schools closed cuts off access to food, medical care and a refuge from abuse.

“There’s ugly sides to parenting, and I think the idea that I’m going to protect my kids first is really beautiful and really ugly,” Boshernitzan said. “How do you balance your desire to give to your kids without taking away from others?”

“We’re about to see what happens when we turn up the volume on families and turn it down on schools,” wrote Paul von Hippel, an associate professor in education policy at the University of Texas at Austin, in an opinion piece this spring on disparities in student learning due to the pandemic.

For privately organized efforts like learning pods, parents are tending to connect with others in their neighborhoods and school zones, already segregated by race and class.

“The question is how far kids who don’t get that, who don’t have access to that, how far are they going to fall behind?” said Tomeka Davis, assistant professor of sociology at Georgia State University. “If schools are already cash strapped, how are they going to remediate kids who have lost that much school to the pandemic?”

Amber Williams-Platt considered putting her 3-year-old son in pre-K in Georgetown ISD this fall, but she’s reconsidering in light of the pandemic. Out of work and in school, she looked for subsidized or free child care options such as Head Start but said she was put on waitlists each time. She used a federal stimulus check to catch up on overdue electricity bills and is living off Social Security payments.

She heard about the learning pods but ruled the idea out quickly as an option for her family. “It has merit, but it takes money to do something like that. You have to have food available for all of the children. You have to have space available,” she said. “If you can’t, you can’t properly share in the duty.”

Texas gave public school districts more flexibility last week on how long they can keep their campuses closed, with educators and parents clamoring that it wasn’t safe to return. Some districts, especially urban and suburban ones where the virus is spreading quickly, may keep their campuses closed to students through the fall and into early winter. Over the last couple of months, state officials have postponed and walked back guidance multiple times, as the politics and health concerns of the pandemic shift — preventing districts from finalizing safety plans or reopening dates.

Largely unsure about their public schools’ plans, hundreds of Texas parents are joining local Facebook groups connecting parents who want to share the responsibilities and costs of hiring instructors to facilitate online learning for their children. The learning pod trend has caught on across the country, especially among upper- and middle-class families with kids in public schools.

Throughout the spring, many school districts struggled to get acclimated to remote learning, facing technical difficulties with their learning platforms and failing to get many students the technology they needed. That put the onus on parents to effectively home-school their kids, in some cases while working from home, or risk them not learning at all.

Boshernitzan and her husband both work full time and are considering a combination of a private child care and a learning pod for their three elementary-age children. A strong proponent of public schools, she plans to send her kids back to Austin ISD in person as soon as it’s safe, and she recognizes how lucky she is to have options.

A whole new industry is springing up around the learning pod trend, with new organizations offering to connect pods of families with teachers or tutors. The Texas Learning Pod, for example, started by a University of Texas at Austin student, links families with college students, offering packages that range from $20 to $55 per hour depending on the number of children and grade levels. And public and private school teachers who are worried about getting sick when schools resume in person are looking for opportunities to teach learning pods.

Sarah Bridle, a parent of five children in Keller ISD in North Texas, is worried her eighth grade son in particular will feel “chained to sitting at the computer” watching teachers livestream lessons. So she’s considering a learning pod where he could socialize with other kids in his grade while completing school assignments.

A stay-at-home mother, she started a Facebook group earlier this month for Keller and nearby Northwest ISD parents who want to create learning pods, getting the idea from a popular San Francisco group called Pandemic Pods and Microschools. Bridle’s group now has more than 900 members.

Bridle has talked with her husband about bringing in one student to join her family’s pod who otherwise wouldn’t be able to afford it, and she’s encouraging other families to do the same. “That’s not always going to be possible, and there’s not an easy fix,” she said. “That’s why we need our public schools system, and we have to find a way to get through this and come through the other side without losing our public schools.”

Chelsey Carter, a co-founder of Bridle's group, is one of an increasing number of parents looking to home-school their children without using resources from the school district, which is virtually unregulated in Texas. Carter is reaching out to other families to form a small group of five or fewer children who hop from home to home and work from the same curriculum.

“While we know the school district is doing everything they can … we feel like there’s just too many unknowns,” said Carter, whose son finished first grade at Northwest ISD last year. “We want to have stability and consistency for our child, and we feel like home school is the best way to do that.” A social worker, she worried her son would have to spend the day tied to a computer if he learned with a school district, which didn’t fit in her schedule. This way, she can share the responsibilities of helping students learn with other parents and potentially pool money to hire a teacher for a couple of days a week.

The Texas Homeschool Coalition said it has seen a major increase in parents inquiring about how to home-school their children, seeking more stability during a rocky year. It has created a tool to help parents withdraw from their public schools and provided resources and free learning packets for parents who want to try it. According to the coalition, about 25,000 students withdrew from public schools to home-school in Texas in 2018.

It’s unclear how much of a blow the drop in enrollment will be for Texas public schools, which are funded based on daily attendance. Texas is requiring school districts to count the number of students who attend remotely and announced last week it will give school districts a break if their attendance drops dramatically during the first 12 weeks.

The uncertainty of where coronavirus hot spots will erupt is especially stressful for parents, who want stability for their children and for themselves. Many know it’s inevitable that some public schools that reopen while the virus is still spreading quickly will have to close again, complicating their decisions.

Rene Coronado and his wife, who both work full time outside the home, will pay $200 per week to keep their 6-year-old son in a private child care center they trust instead of sending him to Grapevine-Colleyville ISD in North Texas. The center had two positive COVID-19 cases this summer, which it handled well, Coronado said, quickly confirming which students had been directly exposed and informing parents as needed.

He received an email from Grapevine-Colleyville ISD last week that included limited details on health and safety protocols for students. “It was just super clear that if one kid gets sick, all the other kids get exposed,” he said. “Even if we couldn’t afford [private child care], which we’re very fortunate we can, we would have to figure it out anyway because the school is going to shut down.”

Disclosure: Facebook and the University of Texas at Austin have been financial supporters of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune's journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

This article originally appeared in The Texas Tribune at https://www.texastribune.org/2020/07/23/homeschool-texas-schools-reopening/.

The Texas Tribune is proud to celebrate 10 years of exceptional journalism for an exceptional state. Explore the next 10 years with us.